Africa begins to emerge as Car Industry Hub

After the European car industry moved much of its production into Eastern Europe, some believe the next step is Africa, both for production and a growing consumer market. Should Germany’s eastern neighbors be worried?

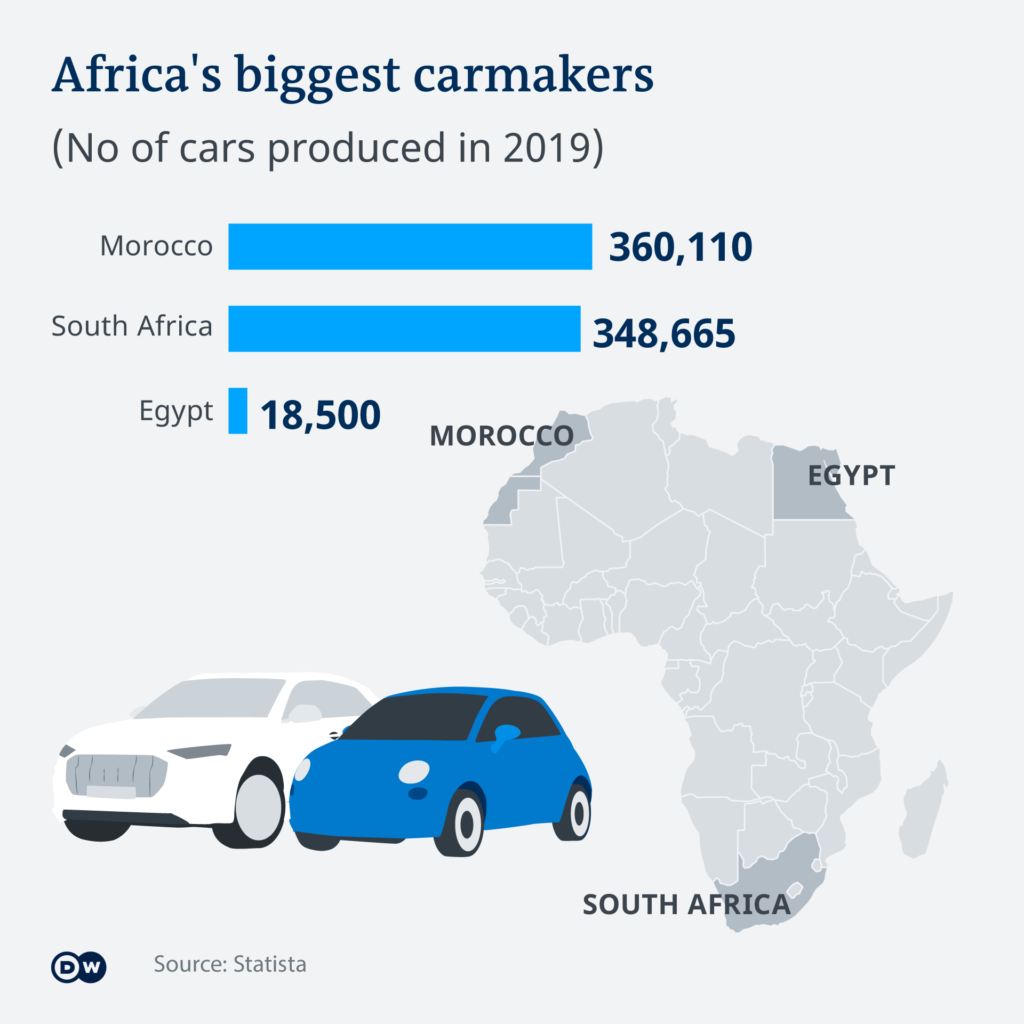

Morocco is an emerging automotive manufacturing hub, while South Africa has a history of carmaking. But multinational vehicle manufacturers are also setting up production plants in Angola, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Namibia, Nigeria and Rwanda, and locally owned African producers are starting out on this road less traveled.

Africa has more than a billion people, 17% of the world’s population, but accounts for only 1% of cars sold worldwide, compared with China’s 30%, Europe’s 22% and North America’s 17%, according to the Paris-based International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers (OICA). Africa has on average 44 vehicles per 1,000 people, compared with the global average of 180 and 800 in the United States, according to consulting firm McKinsey & Company.

Morocco, South Africa lead the way

In 2018, Morocco overtook South Africa as the biggest African exporter of passenger cars with exports in 2019 at $10 billion (€8.5 billion). The two countries mainly make cars for foreign markets, but also have relatively large domestic markets. VW, Mercedes-Benz owner Daimler and BMW are among the biggest car companies in Africa, making up over 90% of all passenger cars produced and a third of the cars sold in South Africa in 2019. Meanwhile, about 80% of the 400,000 cars produced in Morocco are sold to Europe, with France, Spain, Germany and Italy the main destinations.

The Moroccan car industry directly employs 220,000 people, most of whom work for 250 suppliers. Annually, Moroccans buy 160,000 new cars, which is a small number for a population of 36 million.

In September, Stellantis — created in January 2021 after a merger of Fiat Chrysler and PSA — announced that its supermini electric car Opel Rocks-e would be produced at the PSA plant in Kenitra, northeast of Rabat, with a capacity to make 200,000 vehicles a year. Stellantis, the world’s fourth-largest car manufacturer, plans to increase spending on parts made in Morocco from €600 million to €3 billion by 2025.

BYD, a Chinese electric vehicle manufacturer, signed a memorandum of understanding with the Moroccan government to also open a plant in Kenitra, while Hyundai, the Korean carmaker, is reportedly considering setting up shop in Morocco after leaving Algeria.

Meanwhile, STMicroelectronics, a US company based in Casablanca, has just launched manufacturing of the main transmitter for Tesla vehicles in Morocco.

Proximity matters

“The Renault and Peugeot plants in and around Tangier are there because they got super favorable deals — on land, infrastructure, customs facilitation to invest in a country that is a very short ferry ride from Europe,” Joe Studwell, with the Overseas Development Institute in Cambridge, told DW.

Perhaps the main reasons Morocco has been a success story are its location close to European markets and the free trade agreements it has signed with Europe, the US, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and elsewhere.

“This logic does not work for sub-Saharan Africa where it is all about the local markets,” he added.

Locally based suppliers and staff and supplies are also important. Renault, for example, sources parts from seats to axles from local suppliers. Local content accounts for 60% of the final product. Meanwhile, labor costs are about a quarter of those in Spain and lower than in Eastern Europe.

Other African nations on the move

Before Opel’s Moroccan shift, Egypt had been widely expected to become the region’s next leading automotive manufacturing center.

Chinese automaker Dongfeng signed a framework agreement in January with the bankrupt Egyptian state-owned El Nasr Automotive Manufacturing Company to jointly produce electric vehicles in Egypt.

There are also very small production plants in Kenya and Rwanda. In Rwanda, Volkswagen is testing e-mobility.

European production facilities are planned in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Ghana. Ghana wants to limit the import of used and obsolete cars. It is also offering car producers 10 years of tax exemption.

Volkswagen opened its first assembly plant in Ghana in August 2020. Up to 5,000 vehicles are to be assembled there per year, including the Tiguan, the Passat and the Polo. Nissan is also preparing to launch an assembly plant.

In Nigeria, Kenya, Rwanda and Ghana, global carmakers are investing in assembly plants instead of full-fledged production units. In Kenya, a local company, AVA, assembles medium and heavy commercial vehicles for Mitsubishi, Fuso, Scania, Toyota, Hino and Tata.

Africa’s homegrown carmakers

There are also efforts to produce “homegrown” cars with several startups.

In Kenya, Mobius Motors was started in 2009 by British entrepreneur Joel Jackson and now plans to launch an all-terrain vehicle. In South Africa, a joint venture between Mureza and Iran’s SAIPA Group aims to design and manufacture vehicles in Africa for the market on the continent. Kiira Motors also intends to launch a hybrid car in Uganda, while the Innoson is another indigenous brand in Nigeria.

“We see new smaller carmakers in Africa do very specific smaller jobs, and this combined with new technologies such as 3D printing has potential for Africa,” Georg Leutert, director of the Automotive and Aerospace Industries at IndustriALL Global Union, told DW. “This is not dependent on economies of scale and could thus move away from mass production. But there is a problem of brand recognition and service infrastructure, plus the need for big upfront investment,” he added.

“In terms of African firms building African cars, Morocco has so far taken the low-cost route, with the danger of following Mexico into a dead end. That means there is still too little planning to invest in long-term know-how and national capabilities,” Leutert said.

Birkin Cars, a South African-based automobile company, is the oldest in the industry, having started in 1982. The Innoson Vehicle Manufacturing Company was founded by Nigerian-born entrepreneur Innocent Chukwuma and is the first technology company to manufacture cars in Nigeria. The Kantanka Automobile Company was established in Ghana, while Kiira Motors Corporation, a Ugandan automotive company, is interested in creating a hybrid electronic vehicle.

Founded in 2006, the Tunisian company Wallyscar makes 350 convertible SUVs a year. Olfa Seddik from Wallyscar told DW the company was planning to unveil five new models within the next five years and roll out 4,000 cars a year by 2025. “Tunisia suffers from logistical infrastructure and legislation. It will take time before the country manages to resolve these issues,” Seddik said.

“Because of rising wages and automation, it makes increasingly sense to shift some manufacturing back to Europe. This will make it difficult for African countries to really make a breakthrough in car production. Except Morocco on the fringes of the EU and maybe Egypt in the future will benefit from this trend,” said Robert Kappel of the University of Leipzig.

“The markets are too small for both foreign and domestic carmakers and also suppliers, because they would need large quantities to make production worthwhile,” said Kappel.

“[But] in eight to 10 years, a lot can therefore change on the African continent. The market for car production will become bigger, especially as cities with a higher proportion of middle classes grow,” Kappel argued.

“Ghana wants to establish itself as a new hot spot in West Africa. It has identified vehicle assembly and manufacturing of automotive components as a strategic anchor industry. Through this, the government wants to drive industrialization and create new jobs,” he added.

Watch out, Eastern Europe

“Some production, for example wiring and manual stuff, is moving away from Eastern Europe,” Leutert said. “But for [the Czech Republic], Slovakia and Poland there is no real problem, as they are highly skilled, well-established — the costs are still low, and they are close to the German and other European manufacturers.”

“But Romania, Bulgaria and the Balkans could face trouble, given they tend to be less stable in terms of workforce than in North Africa. There is a high turnover of workers, and infrastructure is poor,” he added.

Source: DW